Five Facts to Know About History’s Most Destructive Cyberattack

On Tuesday, June 27, 2017 the world became acquainted with the most destructive malware ever to be deployed. The disaster ushered in a new kind of state-sponsored cyber warfare, with Ukraine the target of a Kremlin-backed effort to frighten those doing business with Ukraine, with which Russia had been in a four-year war. As NotPetya infiltrated most every Ukrainian network, worry spread as it took hold of systems across Europe, the UK and farther.

NotPetya had some recognizable features of its 2016 predecessor, the ransomware Petya, as well as the May 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack. However, the scale, motive and precedent NotPetya set is cause for alarm: $10 billion in damage as well as the incalculable cost of damaged or lost goods, services, and opportunity. Yet, not a single death is attributed to it and oddly, it wasn’t a ransomware attack after all.

Here’s what you need to know about NotPetya, history’s most destructive cyberattack.

1. NotPetya fails to meet the definition of ransomware.

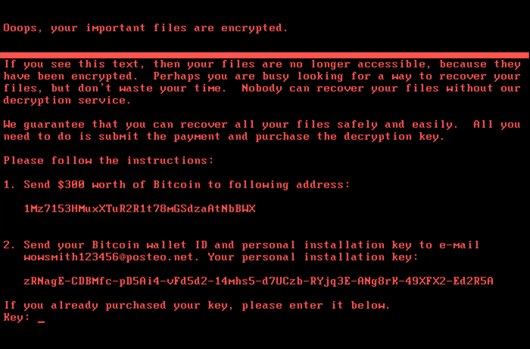

NotPetya takes its name from the ransomware Petya, deployed a year prior, which encrypted files and demanded digital currency payment in exchange for decryption. The name, onscreen ransom note, and a similar cryptoviral profile to Petya make NotPetya similar — but the resemblance ends there. NotPetya’s messages seeking ransom were disingenuous, as there was no authentic decryption-for-payment opportunity. Following a sudden reboot of one’s machine, NotPetya irreversibly encrypted master boot records even for those willing to pay, there was no decryption key. Weeks after the attack there continued to be misdirections from perhaps uninvolved hackers seeking bitcoin in exchange for decrypting files. Consider this: the identifier (a unique number presented on victims’ screens) that victims were told to include in their bitcoin transaction, so perpetrators could remotely decrypt their machine, was found to be...randomly generated. NotPetya was not ransomware.

2. Damage assessments in dollars are enormous, breaking records.

As NotPetya infiltrated Ukraine and began to spread, its footprint grew so far and so quickly that it likely shocked its creators. A former Homeland Security cybersecurity expert, Tom Bossert, statd the damage totaled $10 billion. This is a mere 0.01% of the cost of the March 2018 ransomware attack on the city of Atlanta. Arriving at the $10 billion total of (acknowledged) NotPetya losses is easy considering large, multinational enterprises suffered staggering losses: $870 million lost to pharmaceutical giant Merck, $188 million to maker of Cadbury chocolate Mondel?z ($188 million), and $400 million to FedEx’s European subsidiary TNT Express. Put in perspective, the WannaCry ransomware attack a month prior to NotPetya is estimated to have cost $4 billion to $8 billion.

3. NotPetya’s real-world damage and disruption was far-reaching.

The UK-headquartered global shipping giant Maersk disclosed economic losses of around $250 million to $300 million, said to be greatly underreported. But with 76 ports and 800 vessels the multinational’s helplessness in the face of a total shutdown is a perfect example of the real-world disruption that NotPetya caused. Instantly and simultaneously, every internet-connected device of theirs was infiltrated. These included 45,000 workstations, 4,000 servers, routers, VoIP phones, physical access settings, and other infrastructure. In all, it took 200 Maersk personnel and 400 of their Deloitte contractor counterparts 10 days, working 24/7, to rebuild the Maersk network. Months more were needed to bring about normal software functionality.

Put another way, Maersk — and it is but one such victim — handles one fifth of the world’s shipping. On June 27th and for days later as manual workarounds were instituted, the disaster looked just as you would expect: many miles of 18-wheeler trucks idled outside the largest terminals at the largest, busiest ports in the world, only to be turned away; commercial and humanitarian agricultural goods spoiled; and durable goods for factories and other settings simply failed to ship, choking the economy. Some NotPetya-affected packages still remain unaccounted for.

4. NotPetya used two very nasty Windows exploits.

NotPetya was a modified version of Petya, using two known exploits for older Windows versions: EternalBlue and Mimikatz. The former is a digital skeleton key that was disclosed in a catastrophic NSA data breach in early 2017. It enables outsiders remote access to run their own code. The latter is a proof-of-concept exploit made public in 2011 by Benjamin Delpy, a French security researcher. Delpy’s discovery showed that user passwords on Windows machines persisted in memory, and that they could be extracted from RAM and used for singular or automated, multi-user/multi-machine attacks. Together, these made NotPetya a perfect weapon. It did not require a user action as a trojan would, and it was fast. It simply, and rapidly, traveled from one system to another, accessing admin credentials. A large Ukrainian bank’s network was taken down in 45 seconds, and part of the country’s transit hub was fully infected in 16 seconds.

5. NotPetya’s had deceptively modest origins...and a curious, worrisome deployment method.

NotPetya could superficially be traced to its origin, a small, family-run Ukrainian software business in Kiev. The firm served businesses of all sizes across Ukraine with software such as M.E.Doc (or MeDoc), basically Ukraine’s “TurboTax” that is used by almost every Ukrainian business or tax filer. But don’t look for a David vs. Goliath analogy or even a Pandora’s Box sourced to this Kiev business. Rather, the Kremlin-linked elite hacking group Sandworm targeted the family-owned software business as part of an ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war that has claimed the lives of more than 13,000 Ukrainians since 2014. Sandworm is said to have installed a backdoor into the business’s servers, from which they deployed MeDoc software containing NotPetya — everywhere. (The Ukraine branch of Maersk had MeDoc installed on just one machine.)

Researchers note that NotPetya examined systems for specific profiles, bypassing others, and that no “kill switch” was found, suggesting that those responsible were content to destroy at will and burn the assets they were using. They certainly did a number on the assets of many others, set a precedent, and have changed the way the world views cyberattacks.

That’s five things you now know about NotPetya. To learn more, read Andy Greenberg’s WIRED article which presents the above in far greater detail.